Study Guide: Twelfth Night

If you have any questions or suggestions for improvements in our study guides, please contact Eve Muson, Director, Olney Theatre Institute at 301/924-4485 x 143 or emuson@olneytheatre.org.

Getting the most out of the Study Guide for Twelfth Night

Our study guides are designed with you and your classroom in mind, with information and activities that can be implemented in your curriculum. National Players has a strong belief in the relationship between the actor and the audience because, without either one, there is no theatre. We hope this study guide will help bring a better understanding of the plot, themes and characters in the play so that you can more fully enjoy the theatrical experience.

Feel free to copy the study guide for other teachers and for students. You may wish to cover some content before your workshops and the performance; some content is more appropriate for discussion afterwards. Of course, some activities and questions will be more useful for your class, and some less. Feel free to implement any article, activity, or post-show discussion question as you see fit.

Before the Performance:

Using the articles in the study guide, students will be more engaged in the performance. Our articles relate information about things to look for in the show and information on Shakespeare. In addition, there are articles on the various play adaptations and movies inspired by Shakespeare work. All of this information, combined with our in-classroom workshops, will keep the students attentive and make the performance an active learning experience.

After the Performance:

With the play as a reference point, our questions, and activities can be incorporated into your classroom discussions and can enable students to develop their higher level thinking skills. Our materials address Maryland Core Learning Goals, which are listed on the next page.

The study guide, pre- and post-show discussion questions, and extended activities address specific Maryland Core Learning Goals in English and Essential Learning Outcomes in Theatre, including:

Maryland High School Core Learning Goals: English

Goal 1 Reading, Reviewing and Responding to Texts

1.1.4 The student will apply reading strategies when comparing, making connections, and drawing conclusions about non-print text.

1.2.1 The student will consider the contributions of plot, character, setting, conflict, and point of view when constructing the meaning of a text.

1.2.2 The student will determine how the speaker, organization, sentence structure, word choice, tone, rhythm, and imagery reveal an author’s purpose.

1.2.3 The student will explain the effectiveness of stylistic elements in a text that communicate an author's purpose.

1.2.5 The student will extend or further develop meaning by explaining the implications of the text for the reader or contemporary society.

1.3.4 The student will explain how devices such as staging, lighting, blocking, special effects, graphics, language, and other techniques unique to a non-print medium are used to create meaning and evoke response.

1.3.5 The student will explain how common and universal experiences serve as the source of literary themes that cross time and cultures.

Goal 2 Composing in a Variety of Modes

2.1.2 The student will compose to describe, using prose and/or poetic forms.

2.1.3 The student will compose to express personal ideas, using prose and/or poetic forms.

Goal 4 Evaluating the Content, Organization, and Language Use of Texts

4.1.1 The student will state and explain a personal response to a given text.

4.2.2 The student will explain how the specific language and expression used by the writer or speaker affects reader or listener response.

4.3.1 The student will alter the tone of a text by revising its diction.

4.3.3 The student will alter a text to present the same content to a different audience via the same or different media.

Maryland Essential Learning Outcomes for Fine Arts: Theatre Developed by the Arts Education in Maryland Schools Alliance

Outcome 1: Perceiving, Performing and Responding—Aesthetic Education I.A.1. Identify a wide variety of characters presented in dramatic literature and describe ways they reflect a range of human feelings and experiences

Outcome II: Historical, Cultural, and Social Context

II.A.2. Demonstrate knowledge of appropriate audience behavior in relationship to cultural traditions

II.A.4. Select and discuss the work of a variety of playwrights, critics, theatre commentators, and theorists that represent various cultures and historical periods

II.C.1. Demonstrate familiarity with a variety of dramatic texts and genres

II.C.2. Compare the treatment of similar themes in drama from various cultures and historical periods

Outcome III: Creative Expression and Production

III.A.2. Construct imaginative scripts and collaborate with actors to refine scripts so the stories and their meaning are conveyed to an audience

III.A.3. Develop multiple interpretations for scripts and visual and oral production ideas for presentations

III.A.6. Create and project subtleties of character motivation and behavior using speech, sound, and movement

III.B.6. Study dramatic texts and, using improvisational skills, create extensions appropriate for identified characters and situations

Outcome IV: Aesthetic Criticism

IV.A.1. Use prescribed and self-constructed criteria to evaluate and describe verbally the characteristics of successful ensemble performances and productions

IV.B.1. Analyze dramatic texts and other literature of theatre to identify and describe the presence of theatrical conventions that influence performance

IV.C.1. Identify and describe verbally the primary scenic, auditory, and other physical characteristics of selected theatrical performances

IV.C.2. Write critical reviews of selected theatre performances using established criteria and appropriate language for the art form

Director’s Comments: Staging Twelfth Night

By Clay Hopper

When directing a Shakespeare play, a director usually asks: Where are these people? What time period are they in? The answers to these questions must be very well considered, as they will inform every aspect of the production’s design--from the costumes and sound, to the props and the set. But why not simply set the play in the time in which it was written? What is the purpose of setting a classic play in the present?

The answer to that question is simple: In plays as rich and as large in scope as Shakespeare’s, the choice of place and time period becomes a tool to help illuminate the play’s themes. Viola says, “I am what I am not,” and in Twelfth Night, as in many of his plays, Shakespeare is preoccupied with identity and disguise, and the paradox of discovering the truth only by pretending.

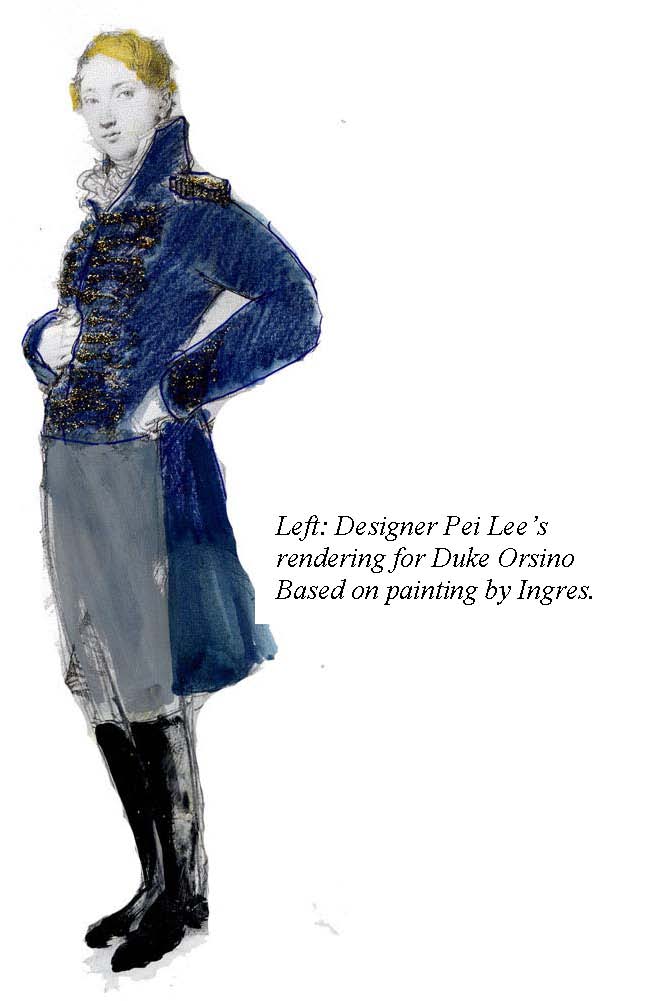

In our production of Twelfth Night, the designers and I were struck by the fact that all of the characters endow others with what they want them to be. It’s as if they are so blinded by their desires that they (consciously or not) use all of their considerable ingenuity and energy to turn other people into what they are not. This allows them to fool themselves into thinking that what they are seeing in others is real. So we decided that the costumes should reflect this notion. The image we started with was that of actors rehearsing the play before they leave the rehearsal hall to go to the stage. They use whatever is around them to make the things that they need. If they need a golden chalice, they use a plastic bottle. If they need money, they use buttons. If they need a candle, they use a flashlight stuck on plate. A piece of tightly wrapped fabric becomes a corset. An apron becomes a tailcoat… You get the idea.

We hope to highlight this idea that runs through the play: that we humans create what we need to be there, especially when what’s there isn’t what we want it to be. But it often turns out that what is there is exactly what we need.

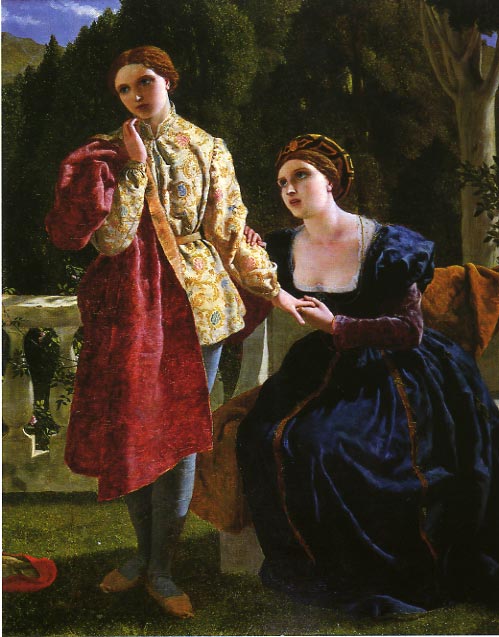

Left: Costume Desiger Pei Lee’s Costume Rendering for Olivia. Based on painting by Ingres.

Your Role as the Audience

The audience plays an integral role in every live performance, and especially in National Players shows. The audience is, in fact, a key element in making live theatre such a special medium and so different from television and film. During a live performance, please keep in mind that the actors onstage can both see and hear the audience. While actors enjoy listening to the audience react, talking and making loud comments only serve to distract not only the actors, but fellow audience members as well.

How to hear Shakespeare

When watching a Shakespearean play, there are many things to keep in mind. Sometimes the language in which Shakespeare writes can be difficult to understand (but once you do, it's really very fun).

First and foremost, you don’t have to understand every word that’s being said in order to understand the play. Don’t get too hung up on deciphering each word; instead, just try to grasp the gist of what each character is saying. After a while, you won’t even have to think about it—it will seem as if you’ve been listening to Shakespeare all your life!

Watch body language, gestures, and facial expressions. Good Shakespearean actors communicate what they are saying through their body. In theory, you should be able to understand much of the play without hearing a word.

So watch the show, let the story move you in whatever way is true to you. Laugh if you want to laugh, be afraid, intrigued, shocked, confused or horrified. The actors want you to be involved in the story they are telling. But please be respectful of the actors working hard to bring you a live performance and to the audience around you trying to enjoy the play. And remember, you will have the opportunity to ask any question about the play or the actors after the show during our Question-and-Answer session.

There is a rhythm to each line, almost like a piece of music. Shakespeare wrote in a form called iambic pentameter. This basically means that each line is made up of five feet (each foot is two syllables) with the emphasis on the first syllable. You can hear the pattern of unstressed/stressed syllables in the line, “If music be the food of love, play on.” Listen for this in the play as it adds a very lyrical quality to the words.

Read a synopsis or play summary ahead of time. Shakespeare’s plays, especially his comedies, involve many characters in complex, intertwining plots. It always helps to have a basic idea of what’s going on beforehand so you can enjoy the play without trying to figure out every relationship and plot twist.

Enjoy it! Shakespeare’s comedies are actually funny. Find the humor, laugh, and have a good time!

Left: Edmund Blair Leighton’s 1888 painting Olivia.

Who’s Who?

Orsino’s Household

Duke O r s i n o is a romantic nobleman of Illyria. He is in love with Olivia— although some may argue that he is in love with the idea of being in love. Olivia does not return the duke’s affections, and as a result he wallows in melancholy.

C u r i o is Orsino’s servant. Although he tries to serve him as best he can, he is not as close to the duke as the newly arrived Cesario.

The Shipwrecked

V i o l a ( C e s a r i o ) is a young woman of aristocratic birth and the twin sister of Sebastian. She dresses as a young man named Cesario in order to act as page to Duke Orsino, and she quickly becomes his close confidante.

S e b a s t ia n is the twin brother of Viola. He is mistaken for Cesario when he enters Illyria, and mayhem ensues.

A n t o n i o is a sea captain who rescues Sebastian after the shipwreck. He accompanies Sebastian in Illyria— because he cares for him and wishes to protect him— but this is dangerous for Antonio because he is a wanted man in Illyria.

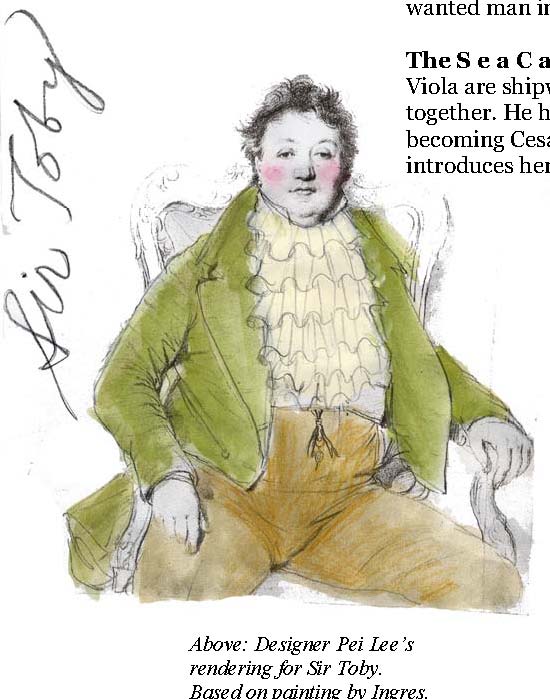

The S e a C a p t a i n and Viola are shipwrecked together. He helps her in becoming Cesario and introduces her to the duke.

Olivia’s Household

O l i v i a is a wealthy countess pursued by Orsino and Sir Andrew. Olivia is in mourning over the death of her brother, and she vows to hold to her mourning period for seven years. Olivia falls in love with Viola when she is disguised as Cesario.

S i r Toby B e l c h is Olivia’s uncle. She does not approve of his chaotic, drunken behavior, but Sir Toby has an ally in the household as well—Maria.

M a r i a is Olivia’s quick-witted maid. She runs the household and schemes with Sir Toby.

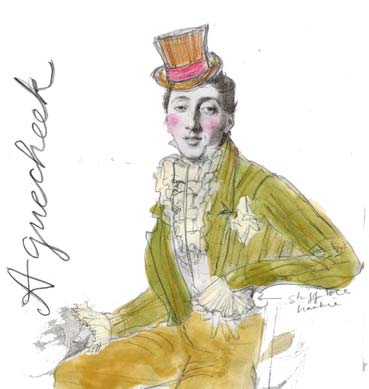

S i r A n d r e w A g u e c h e e k

is a nobleman who is drawn into schemes with Sir Toby and Maria while trying to win Olivia’s heart. Although he believes himself to be witty and brave, he is an utter fool.

Fe s t e is a jester and musician who lends his services to Olivia, and to Orsino as well. He is a fool by profession, but he is very perceptive of peoples’ inner natures. Wise counsel is often concealed within his entertainment.

M a l v o l i o is Olivia’s ambitious—and vain—steward. He is quite impressed by his own virtue and harbors a secret love for Olivia. His disdain for fun, along with his haughtiness, earns him the enmity of Maria, Sir Toby and Sir Andrew.

The F r i a r, or priest, is called upon by Olivia so that she can be married to Cesario.

Twelfth Night Synopsis

With a plot full of hidden love, foolery, music, and an ultimately triumphant ending, Twelfth Night has delighted audiences for 400 years. Twelfth Night, called “the funniest of Shakespeare’s play,” by critic Harold Bloom, was the last of his light comedies before venturing into a line of tragedies and darker comedies known to modern scholars as “problem plays.”

Twelfth Night opens as Orsino, duke of Illyria, speaks of his consuming passion for the beautiful Olivia. She, however, has rejected all of his advances because she is in mourning for her recently deceased brother.

Meanwhile, Viola and a sea captain, who have been rescued from a shipwreck, land on the coast of Illyria and Viola believes that her twin brother, Sebastian, has been killed in the wreck. Defenseless, Viola decides to disguise herself as a young man and seek service with Duke Orsino. Unbeknownst to her, however, Sebastian has been rescued by Antonio, another sea captain, and has landed in further up the coast. He begins to make his way to Illyria with Antonio.

Right: Imogen Stubbs as Viola in disguise and Helena Bonham Carter as Olivia in a 1996 film version of Twelfth Night.

Under the name Cesario, Viola gains Orsino’s favor and, although she falls in love with Orsino herself, consents to be his go-between with Olivia. In Olivia’s household, the only servant who seems to enjoy the enforced mourning for Olivia’s brother is the humorless, uptight Malvolio. Olivia’s kinsman, Sir Toby Belch, and his friend Sir Andrew Aguecheeck (one of Olivia’s suitors) spend their nights carousing, aided and abetted by Maria, Olivia’s maid.

Cesario (Viola) arrives to carry “his” master’s pleas to Olivia, but to complicate matters, Olivia finds herself falling in love with Cesario.

That night, Sir Toby, Sir Andrew, and Feste, Olivia’s fool, drink and revel. Maria begs them to be quieter; but when Malvolio comes in and reprimands them for their carelessness, they all decide to exact revenge on him. Maria forges a note that appears to have been sent by Olivia to a lover; when Malvolio receives it, he is sure that it is meant for him. The note instructs him to be surly with servants, to wear yellow stocking with cross-garters, and to smile continuously in Olivia’s presence. The plot against Malvolio works to perfection: his strange antics in following the instructions of the note cause him to be imprisoned in a dark room as insane.

Sir Toby, making more mischief, sets up a duel between Sir Andrew and Cesario, on the pretext that Cesario is a rival suitor for Olivia’s hand. As the two unwilling duelists prepare to fight, Antonio rushes in and, believing that Cesario is Sebastian, prevents the duel. However, when officers seize Antonio as a former enemy to Illyria, he begs Cesario to vouch for him. Upon Cesario’s denial that “he” knows Antonio, the good captain’s faith in human nature is shaken. However, Viola, upon reflection, realizes that the name “Sebastian” has been spoken and hopes that her brother may be alive.

Convinced that Cesario is a coward, Sir Andrew rushes out to challenge the page; but instead of Cesario he finds Sebastian. Olivia’s entrance breaks up the fight, and mistaking Sebastian for Cesario, invites him into her house, and then proposes marriage to the smitten Sebastian.

The Duke and Cesario arrive before Olivia’s house, where they meet Antonio. When Antonio again reproaches Cesario — whom he still believes to be Sebastian—the Duke is completely baffled by Antonio’s insistence that the young man has just arrived in Illyria. Olivia enters and speaks lovingly to Cesario. Orsino is naturally angry at what he supposes has been Cesario’s treacherous attempt to win Olivia’s affections, and when a priest swears that he has recently married the couple, Orsino becomes furious.

Sir Andrew and Sir Toby, meanwhile, have inadvertently picked a fight with Sebastian (believing him to be Cesario) and both enter wounded and bleeding. However, when Sebastian appears almost immediately, all the characters realize that they have been dealing with almost-identical twins. Matches are made all around: Sir Toby has married Maria, Orsino offers to marry Viola, and Olivia and Sebastian remain together. Everyone is happy except Malvolio, who vows revenge on the whole group.

Adapted from Synopses of Shakespeare’s Complete Plays.by Nelson A. Ault and Lewis M. Magill, Littlefield, Adams and Co., 1962.

William Shakespeare: The Man Behind the Words

Throughout the decades, William Shakespeare has come to be revered as one of the greatest playwrights in the history of theatre. Not only are his works continually performed all over the world, but numerous theatres exist solely to produce his plays.

Shakespeare was born in Stratford-upon-Avon, England on April 23, 1564. He came from a family described as “honest, hard-working, middle-class stock.” He received minimal education and by the time he was 18 he was married to a girl by the name of Anne Hathaway. His first daughter, Susanna, was born the next year, followed by his twins, Hamnet and Judith, in 1585.

In the late 1580s, Shakespeare moved to London (96 miles away — about a four-day walk — from Stratford) in an attempt to financially support his family through the theatre. He began as an actor, but soon started writing plays and poetry as well. By 1592, he was known throughout the London theatre scene as an up-and-coming young artist.

In the spring of 1594, Shakespeare joined a company of actors known as the Lord Chamberlain’s Company, called such because they were under the patronage of the Chamberlain to Queen Elizabeth I. The troupe began performing at the Theatre, but when their lease on the land expired, they took matters into their own hands. Illegally dismantling the Theatre and carrying its timbers across the Thames River, the company built what would become one of the most famous theatres in England: the Globe.

Soon after the move, Shakespeare became the principal playwright for the company, providing actors with approximately two plays a year. He was also highly involved in the management of the troupe and received a share of all profits. During this period, Shakespeare gained recognition as one of England’s premiere playwrights, while each of his plays received tremendous popular acclaim.

In 1603, when King James I was crowned after Queen Elizabeth’s death, Shakespeare’s troupe became known as the King’s Men and performed often in the King’s court. They were now recognized as Grooms of the Chamber, or minor court officials. At this time, Shakespeare gave up acting completely and became solely a playwright/manager for the company.

In 1611, Shakespeare retired to his home in Stratford, where his wife and children had remained all these years, supposedly to spend time in “ease, retirement, and the conversation of friends.” By this point, he had come to be quite a wealthy man and was able to live comfortably.

Shakespeare died on April 23, 1616. Those who knew him remembered him as “a handsome wellshaped man, very good company, and of a ready and pleasant wit.” Today he is remembered for his literary genius and timeless stories.

Shakespeare’s Theatre

The theatre scene that Shakespeare found in London in the late 1580s was very different from anything existing today. Because he was directly affected by and wrote specifically for this world, it is very important to understand how it worked.

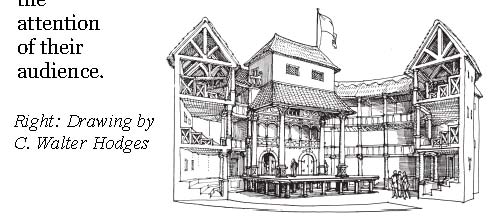

The Performance Space

The Globe Theatre was a circular wooden structure constructed of three stories of galleries (seats) surrounding an open courtyard. It was an open-air building (i.e. no roof ), and a rectangular platform projected into the middle of the courtyard to serve as a stage. The performance space had no front curtain, but was backed by a large wall with one to three doors out of which actors entered and exited. In front of the wall stood a roofed house-like structure supported by two large pillars, designed to provide a place for actors to “hide” when not in a scene. The roof of this structure was referred to as the “Heavens.” The theatre itself housed up to 3,000 spectators, mainly because not all were seated. The seats in the galleries were reserved for people from the upper classes who came to the theatre primarily to “be seen.” These wealthy patrons were also sometimes allowed to sit on or above the stage itself as a sign of their prominence. These seats, known as the “Lord’s Rooms,” were considered the best in the house despite the poor view of the back of the actors. The lower-class spectators, however, stood in the open courtyard and watched the play on their feet. These audience members became known as “groundlings” and gained admission to the playhouse for as low as one penny. The groundlings were often very loud and rambunctious during the performances and would eat (usually hazelnuts), drink, and socialize as the play was going on, as well as shout directly to the actors on stage. Playwrights at this time were therefore forced to incorporate lots of action and bawdy humor in their plays in order to keep the attention of their audience.

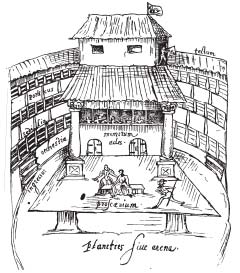

Left: Sketch of the original Globe Theatre by Arend van Buchell

Left: Sketch of the original Globe Theatre by Arend van Buchell

The Performance

During Shakespeare’s day, new plays were being written and performed continuously. A company of actors might receive a new play, prepare it, and perform it every week. Because of this, each actor in the company had a specific type of role that he normally played and could perform with little rehearsal. One possible role for a male company member, for example, would be the female ingenue. Because women were not allowed to perform on the stage at the time, young boys whose voices had yet to change generally played the female characters in the shows. Each company (composed of 10 – 20 members) would have one or two young men to play the female roles, one man who specialized in playing a fool or clown, one or two men who played the romantic male characters, and one or two who played the mature, tragic characters.

Along with the “stock” characters of an acting company, there was also a set of stock scenery. Specific backdrops, such as forest scenes or palace scenes, were re-used in every play. Other than that, however, very minimal set pieces were present on the stage. There was no artificial lighting to convey time and place, so it was very much up to audience to imagine what the full scene would look like. Because of this, the playwright was forced to describe the setting in greater detail than would normally be heard today. For example, in order to establish time in one scene in Twelfth Night, Shakespeare has Sir Toby say, “Approach, Sir Andrew; not to be abed after midnight is to be up betimes.” The costumes of this period, however, were far from minimalist. These were generally rich and luxurious, as they were a source of great pride for the performers who personally provided them. However, these were rarely historically accurate and again forced the audience to use their imaginations to envision the play’s time and place.

“O Spirit of Love, how quick and fresh art thou”

Orsino opens the play with one of Shakespeare’s often-quoted speeches. He is in an agony of emotion—for the onset of love turns us all into adolescents, regardless of age—and he is consequently unstable. He sets both the tone and the intensity of feeling in the play, but he is far from the only lovesick character. Lovesickness seems to sweep like an epidemic through the play, or, to use the play’s images, like a madness or a binge.

Watch how the love infection spreads: Viola catches it as soon as she joins Orsino’s court, for she falls in love with him in three days. Olivia catches the sickness from Viola during their first interview. And Sebastian catches the plague of love as soon as he meets Olivia.

A number of other characters speak in the language of love, or try to do so, for both Sir Andrew and Malvolio consider themselves wooers of Olivia. Sir Andrew’s love talk is distinguished by its poverty and ineptitude. He wants to be eloquent, but he has slender means.Malvolio—though mostly “sick of self-love,” as Maria notes—believes Olivia loves him and abandons his pride to pursue her, dressed in his yellow garters with a smile on his face. Even Antonio’s passionate dedication to Sebastian uses love’s rhetoric, for the male friendship bond in the Renaissance was more forthright andemotional than today.

Viola’s love must stay unspoken and secret, yet she cannot help but express her feelings and her ideas about love. In fact, her disguise allows her to speak more freely, and to discover what she really wants. Orsino is drawn toCesario as the only person with whom he can discuss love, and they debate the comparative fidelity of men and women in love. Orsino makes big claims, but Viola wins the argument not only with her words, but with her actions.

Where is Illyria?

Illyria, the setting of Twelfth Night, has been a subject of critical discussion for decades. Where exactly is this place, and why did Shakespeare choose it as a setting for this play?

- Illyria really does exist. It is a region on the east coast of the Adriatic Sea along the Northwest Balkans, said to be the ancestor of modern-day Albania. In Shakespeare’s time, it was known for its wild riot, drunkenness, and piracy (aptly fitting the play’s themes of revelry and trickery).

- In Ovid’s Metamorphoses (a known source of inspiration for Shakespeare), there is a mention of Illyria in the line, “Upon the coast of Illirie his wife and he were cast.” This has lead scholars to believe that perhaps Shakespeare’s characters and setting were inspired by those of Ovid, who lived near the actual Illyria.

- Many critics, however, argue that Illyria is meant to represent an imaginary, distant land; a place out of the world and out of time, such as the forest in Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream or Arden in As You Like It.

Gender Identity and Disguise in Shakespeare

The element of gender identity and disguise is prominent in many of Shakespeare’s plays. In Twelfth Night, Viola disguises herself as a man, Cesario, for protection in the new, strange land of Illyria. She believes that her twin brother, Sebastian, has drowned, and chooses to disguise herself

for her protection and to find work. But her handy solution turns out to be her biggest problem—how can her love for Orsino ever be requited if she is a man? How can Olivia’s love for Cesario ever be requited if Cesario is in fact a woman?

Viola states that although she created this problem, there is no way she can fix it – “O time, thou must untangle this, not I. / It is too hard a knot for me t’untie.” It seems very “womanly” to not try to fix a major problem that she was a part of, instead choosing to give responsibility for solving the problem to an outside force. As critic Ann Barton writes, “Even her boy’s disguise operates not as a liberation but merely as a way of going underground in a difficult situation, of

waiting to see what Time will bring.” However, this passage also proves Viola’s maturity: She knows she cannot mend these troubles, and she also recognizes that fate rules all.

Paradoxically, it is only in the disguise that Viola is free of the patriarchal boundaries that confine and oppress women in her world. As Cesario, she is able to debate freely with Orsino and become his peer and partner. Only by pretending can she discover and realize her authentic identity.

There is no small amount of controversy over the exact dates when The Bard wrote his plays—just as there is controversy over his life itself. The following list, however, represents the dates that are accepted by most scholars:

| 1589–90 Henry VI, Part 1 | 1596 A Midsummer | 1602–03 All’s Well That Ends |

| 1590–91 Henry VI, Part 2; | Night’s Dream | Well |

| Henry VI, | 1596–97 The Merchant of | 1604 Measure for Measure; |

| Part 3; Richard III | Venice | Othello |

| 1592–94 The Comedy of | 1597 Henry IV, Part 1 | 1605 King Lear |

| Errors | 1598 Henry IV, Part 2 | 1606 Macbeth |

| 1593–94 Titus Andronicus; | 1598–99 Much Ado About | 1606–07 Antony and |

| The Taming of the Shrew | Nothing | Cleopatra |

| 1594 The Two Gentlemen of | 1599 Henry V; Julius | 1607–08 Coriolanus; Timon of |

| Verona | Caesar; As You Like It | Athens; |

| 1594–95 Love Labor’s Lost | 1599–1600 Twelfth Night | Pericles, Prince of Tyre |

| 1594–96 King John | 1600–01 Hamlet | 1609–10 Cymbeline |

| 1595 Richard II | 1601–02 Troilus and | 1610–11 The Winter’s Tale |

| 1595–96 Romeo and Juliet | Cressida | 1611 The Tempest |

The Fool

How many times have you seen the class clown come out on top in difficult situations? It happens all the time in William Shakespeare’s plays and Feste in Twelfth Night is no exception. Feste is the storyteller of this comedic drama, mainly through song; he is the only character besides Viola who moves back and forth from Orsino’s court to Olivia’s court, and he knows more about the events and action in the play than anyone else. He also predicts the outcome of the play—again through song — in the beginning of the second act: “Trip no further, pretty sweeting, / Journeys end in lovers meeting.” Feste foresees the last scene where Orsino claims Viola as his bride and Olivia finds out that she married Viola’s twin brother Sebastian. Feste, by traveling between the two main areas of action, is not emotionally involved in the drama between the different characters and acts as an observer and as a tie between the two houses.

Viola is the only character who recognizes how perceptive Feste actually is: “This fellow is wise enough to play the fool.” Feste, along with a few other characters (Olivia’s gentlewoman Maria and Olivia’s uncle Sir Toby Belch) play tricks on Olivia’s steward Malvolio, the play’s actual fool. The egotistical Malvolio shuns songs, playing, and drinking all hours of the night, but is quite excited when he receives a declaration of love…but he doesn’t know the letter isn’t from who he thinks it is. Malvolio is convinced that the letter is from Olivia when Maria actually wrote it, at the goading of Feste and Sir Toby. Malvolio proceeds to wear cross-gartered yellow stockings and smile like an idiot because the letter states that those are the things that will tell Olivia that Malvolio loves her back. In the end, Feste is proven a wise man while Malvolio storms off in anger, the play’s true fool.

The First Twelfth Night

The phrase “Twelfth Night” actually refers to the last night of the Feast of the Epiphany, a 12-day celebration of the Christmas holidays and the journey of the Magi to bring gifts to the infant Christ. The Twelfth Night celebration occurred on January 6th every year and was known as a feast of misrule, eating, and drinking during which masques and revels were presented. Historical documents show that on January 6th (Twelfth Night) in 1601, Queen Elizabeth I of England held a royal celebration in her court to entertain the visiting Duke Orsino of Bracciano. The Lord Chamberlain’s Men (Shakespeare’s company) were paid to perform a play at this particular celebration. These facts lead scholars to believe the first performance of Twelfth Night may have been at this celebration. It would make sense for the play’s name to refer directly to its occasion, as well as the name of the queen’s guest in one of its main characters.

Rather than creating a play to be performed at the Globe Theatre like so many of his others, Shakespeare would have written it specifically for the court in which it would be presented.

Looking back on that first performance of Twelfth Night, it is difficult to know if this is in fact the exact scenario that unfolded as Shakespeare penned his famous comedy. However, as scholars have found, it is exciting to piece together what might have been and what forces could have prompted the creation of such a play.

Below: Designer Pei Lee’s rendering for Maria Based on painting by Ingres.

Pre-Show Discussion Questions

- Discuss your previous experiences with Shakespeare and his works. Were they at all difficult to understand, or tedious to read or view? Do you find the language in Shakespeare beautiful and poetic, or does the archaic language just bring about frustration and hinder understanding? What has helped make the plays more accessible and relevant to your own life? Having read the synopsis of Twelfth Night, what scene and/or relationship are you most excited to watch?

- Messages and messengers play an important role in Twelfth Night. More often than not, the messages are the source of misinformation or confusion. Have your students write a brief description of something that happened recently in the classroom, and then read the descriptions aloud. See if the students can guess who wrote which description.

- If you are able to read the play before the performance, write a short description about or discuss relationships between the following character pairs: Sir Toby and Maria; Malvolio and Olivia; and Antonio and Sebastian. Keep these descriptions for use after you see the performance.

Post-Show Discussion Questions

1. Twelfth Night is hailed as one of Shakespeare’s best comedies. What elements of the play make it so entertaining? Think about characters, relationships, plot devices, language, etc. What about

Below: Designer Pei Lee’s the people in Twelfth Night makes them so funny? Why do we, rendering for Sir Andrew Aguecheek as theatergoers, love to watch people in sticky situations and find Based on painting by Ingres. it entertaining? How does Shakespeare get an audience to laugh out loud?

- The time in which Shakespeare was writing is much different from today’s world. How do you think the relations between people and the themes in Twelfth Night compare and contrast to today? Can you think of a theme similar to one in Twelfth Night—such as hidden love, mistaken identity, or the wise fool— you have heard about recently?

- How does knowing about the configuration of the Globe Theater and the way in which Shakespeare’s plays were performed there change your understanding of his plays? Do you find any explanations in this information for why he wrote his plays the way he did? Think about the actual experience of attending a theatre in Shakespeare’s day. Are there any similarities to a theatre you would attend today? What are the major differences? Which style appeals more to you?

- Twelfth Night is a romantic comedy, and as such, love is the primary focus. Why do you believe each of the characters falls in love? Was it because of the situation itself, because of the personality of the other person, or because of his or her outward appearance? Support you argument with evidence from the play.

- Although the play offers a happy ending, several of the characters grieve or suffer pain because of their love. Make a list of the characters who suffer due to love in the play, and discuss or write a brief description of why. How closely related are the ideas of love and suffering? Does anyone fall in love in this play who doesn't suffer? How does this relate to your own life? Do some of the characters even enjoy their own suffering? Given that this is a romantic comedy, what was Shakespeare’s purpose in showing the pain love can cause? Overall, what do you believe The Bard was saying about life and love in Twelfth Night?

- Gender ambiguity in Shakespeare is a never-ending area of discussion. When Shakespeare’s plays, including Twelfth Night, were first produced, all-male casts performed them. Also, he wrote many plays where female characters disguised themselves as men and sometimes, female characters adopted the gender roles of the male. Why does Viola disguise herself as a boy in Twelfth Night? How are women thought of and treated in the play? Are women treated differently today? How so?

- Shakespeare’s Fools are often the most complex characters in his plays, and Twelfth Night’s Feste is no exception. Is Feste a wise Fool, a foolish Fool, or a bit of both? How does his role help to develop the other characters in the play, such as Olivia, Sir Toby and Malvolio? How is he different than the other characters? How does Feste influence the plot? Does he serve a role between the play and the audience? What are his overall purposes in the production?

- What do you find humorous about the treatment of Malvolio? Do you sympathize with the character, or is he too unlikable to pity? Relating the manipulation of Malvolio to situations in current movies (i.e. Meet the Parents, Home Alone), what is so funny about cruelty and human misfortune? What makes it entertaining to watch?

- Refer to the descriptions of the character relationships that you made before the performance (between Sir Toby and Maria; Malvolio and Olivia; and Antonio and Sebastian). Now that you have seen the play performed, have your perceptions of these relationships changed? What different or new aspects did you notice in each of the relationships?

- A person’s perception of events is often shaded by their own point of view. Have the class split into pairs or groups. Each group member will pick a different character from the play and assume that character’s identity (and that character’s point of view). Have each group then debate the events of the play, with each student maintaining the point of view of the character they have chosen. Does each character see the events of the play in a different light? If so, how was their point of view different? What are the reasons for the differences?

Adaptations

The proof of the resilliance and continued power of William Shakespeare’s work is in the many adaptations that his plays have inspired. From movies that use the original dialogue to those that take Shakespeare’s situation as a springboard for contemporary characters, the number of Shakespeare adaptations is still growing. Here is a short list of some of the movies that have been created from the words of William Shakespeare.

True to the text, time and setting:

Early 20th Century actor Sir Laurence Olivier starred in many film productions of Shakespeare, including the film production of Hamlet (1948). In Olivier’s productions, all of the aspects of Shakespeare’s work are kept the same. Olivier is probably the most famous actor and interpreter of Shakespeare.

Film director Roman Polanski did an adaptation of The Tragedy of Macbeth (1971) in which he didn’t change the setting, the time period, or the language. This adaptation is probably one of the darkest, because Polanski directed the film exactly one year after the Manson Family murdered his pregnant wife, Sharon Tate.

Theatre and film director Julie Taymor has directed Shakespeare plays on the stage as well as films, such as The Tempest (1986), and The Tragedy of Titus Andronicus (1999), an imaginatively staged piece that cut the script but retained Shakespeare’s words, setting, and the time period.

Twelfth Night (1996). This is a film adaptation of the play, directed by Trevor Nunn and starring Helena Carter, Nigel Hawthorne, and Ben Kingsley as the multidimensional Feste.

Irish actor Kenneth Branagh is also famous for directing different film versions of Shakespeare’s work, including Much Ado About Nothing (1983), Hamlet (1996), Twelfth Night (1988), and As You Like It (2007). He also starred in Hamlet.

Actor/producer Mel Gibson starred in the 1990 version of Hamlet directed by Franco Zeffirelli and also stars Helena Bonham Carter as Ophelia.

Adaptations that change the time period:

Famous actors Rupert Everett, Calista Flockhart, Kevin Kline, and Michelle Pfeiffer star in an adaptation of A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1999). This lavish adaptation takes place in the 1930s. Some of the script is cut, but the actors still keep to the original text.

Probably the most popular film adaptation of recent years is The Tragedy of Romeo and Juliet starring Leonardo DiCaprio and Claire Danes and directed by Baz Luhrmann (1996). This adaptation shifts the action to modern-day Verona and mixes modern music with Shakespeare’s original language, and used guns instead of swords for the battles.

Another popular film adaptation of Shakespeare is The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark (2000) with Ethan Hawke as Hamlet, as well as Julia Stiles and Bill Murray, set in present-day Manhattan. Though the script is cut, Shakespeare’s language is preserved.

Adaptations that only preserve the situation:

O, a modern-day version of Shakespeare’s Othello, was directed by Tim Blake Nelson and starred Julia Stiles, Mekhi Phifer, and Josh Hartnett, and translates Shakespeare’s story of jealousy and murder to a private high school.

The popular film 10 Things I Hate About You (1999), starring Julia Stiles, is an adaptation of Shakespeare’s play The Taming of the Shrew. The play takes place in sixteenth-century Padua, Italy while the movie is set in a modern day California and follows the dating troubles of its characters in contemporary language.

She’s the Man, directed by Andy Fickman, is a modern-day Twelfth Night in which Viola poses as her twin brother at his boarding school, getting very close to his roommate Duke.

For more information on Shakespeare adaptations, visit the International Movie Database at www.imdb.com.

Further Reading & Research

Twelfth Night reading companions

Twelfth Night, or What You Will (Arden edition) by William Shakespeare

Outlines of Shakespeare’s Plays by Karl J. Holzknecht, Raymond Ross, and Homer A. Watt

Synopses of Shakespeare’s Complete Plays

by Nelson A. Ault and Lewis M. Magill

William Shakespeare: A Textual Companion by Stanley W. Wells, Gary Taylor, John Jowett, and William Montgomery

Critical essays

Modern critical interpretations of Twelfth Night edited by Harold Bloom

Twelfth Night: Contemporary Critical Essays edited by R.S. White

Twelfth Night Critical Essays edited by Stanley Wells

The Fools of Shakespeare by Frederick Warde

Shakespeare

Will in the World: How Shakespeare Became Shakespeare by Stephen Greenblatt

Shakespeare our Contemporary by Jan Kott

Shakespeare After All by Marjorie Garber

Shakespeare: A Life in Drama by Stanley Wells

The Riverside Shakespeare by William Shakespeare et al. Houghton Mifflin; 2nd edition; 1997. If you love Shakespeare, then this is the book to own. It is a respected collection of all Shakespeare’s work.

Shakespeare’s Theatre

The First Night of Twelfth Night by Leslie Hotson

The Twelfth Night of Shakespeare’s Audience by John W. Draper

Shakespeare’s Theatre by Peter Thomson

The Shakespearean Stage, 1574 – 1642 by Andrew Gurr

Websites

www.shakespeare-literature.com and www.absoluteshakespeare.com contain the complete texts of Shakespeare’s plays (for free viewing) as well as many links to study resources.

www.shakespeare-online.com is an excellent repository of information on Shakespeare and it is updated frequently.

www.bardweb.net is another large repository of Shakespearean information. However, this site also contains excellent summary information on Elizabethan England, which is invaluable to any study of The Bard’s works.

www.shakespeareauthorship.com is a website dedicated to the proposition that Shakespeare wrote Shakespeare.

www.bbc.co.uk/education/asguru/english/ 08sh akespeare/index.shtml Hosted by the BBC, this website has an interactive quiz on Shakespeare as well as several questions about Twelfth Night.

www.folger.edu/Home_02B.html is the website of the Folger Shakespeare Library. It contains resources for teachers that include lesson plans and interactive activity guide.

Twelfth Night: Extended Lesson Plans

Curriculum Plan #1

Shakespeare Scavenger Hunt: Listening Closely

Objectives: Some students have trouble focusing during a play. This exercise is intended to keep them involved in the characters, who is speaking, and what is being said. It adds an extra level of excitement to watching the production. In addition to following the story, they are now challenged to locate individual lines, identify what is going on in the scene that causes those lines to be said, and to find greater connection with the text as it comes to life. The exercise will challenge higher lever students to connect with the characters on a personal level. This should help them to find meaning for themselves within the monologues. It should inspire them to view the play as a living thing they can connect to personally and introduce them to the fun of exploring the text.

Materials Needed: Their assigned line from the choices on the following pages (or any others you might choose), a copy of the play, a notebook/piece of paper, and a pencil.

This lesson will take one or two class periods.

Suggested Lesson Plan 1) Assign each student a quote from the play. A list of suggested quotes has been provided on the following page(s). 2) Feel free to give students a general idea of the quote's placement within the play and its general meaning, but do not paraphrase it for them or pinpoint the quote's location. 3) Their challenge will be to listen to the play and find their quote used during the performance. 4) Once they have located their quote, their assignment is to write down who said it and who they said it to. Students should then write down why the character said that specific line and what they think it means. 5) Back in the classroom have each student say their quote out loud and remind their fellow students of the character, the scene, and the situation in the play from which their quote was taken. 6) If a student had difficulty locating their quote, perhaps a fellow student with a quote from the same monologue or scene can help them out. Use the master list on the following pages to find nearby quotes to jog their memories.

For higher level students or if you have more time:

1) As before, the students should be assigned a line or quote from the play. They must locate their line, take note of the character speaking the line, who they are saying it to, and what is going on in the play at that point. 2) After the performance (either as homework or back in the classroom) students should find their quote in the play itself. They should learn the monologue or scene from which the line was taken (10-14 lines suggested). 3) Have your student paraphrase the monologue, putting it into their own words- the more slang the better). 4) Students should then bring in their monologue or scene, complete with paraphrase on a separate sheet. Have students remind their fellow students of the point in the play from which their piece is taken. Then they should perform their piece of the play.

Assessment:

Your students should find a greater connection with the text and the characters. They should be able to identify their lines as they are spoken on stage and identify the characters who speak them. If they can go even further and identify what the character meant and what the situation was you and they have done an excellent job! For higher levels, students should be able to use the paraphrase to perform their own interpretation of the monologue or scene. If they have connected with the work, their meaning and intentions should be clear in the performance.

Shakespeare Scavenger Hunt: Quotations

| Quotations | Quotations Key |

| If music be the food of love, play on; Give me excess of it, that, surfeiting, The appetite may sicken, and so die | Orsino: (Act I, Scene i) -- Speech to Curio/ Musicians |

| The element itself, till seven years' heat, Shall not behold her face at ample view; | Valentine: (Act I, Scene i) -- Speech To Orsino |

| What country, friends, is this? | Viola: (Act I, Scene ii) -- Scene with Sea Captain |

| Be you his eunuch, and your mute I'll be: When my tongue blabs, then let mine eyes not see. | Captain (Act I, Scene ii) -- Scene with Viola |

| By my troth, Sir Toby, you must come in earlier o' nights: | Maria: (Act I, scene iii) -- Scene w/ Sir Toby |

| Confine! I'll confine myself no finer than I am: these clothes are good enough to drink in; | Sir Toby: (Act I, scene iii) -- Scene w/ Maria |

| Whoe'er I woo, myself would be his wife. | Viola: (Act I, scene iv) -- Monologue to audience/ herself |

| Many a good hanging prevents a bad marriage; | Feste: (Act I, scene v) -- Scene w/ Maria |

| The lady bade take away the fool; therefore, I say again, take her away. | Feste: (Act I, scene v) -- Speech to Olivia |

| I marvel your ladyship takes delight in such a barren rascal: | Malvolio: (Act I, scene v) -- Speech to Olivia |

| Make me a willow cabin at your gate, And call upon my soul within the house; | Viola: (Act I, scene v) -- Speech to Olivia |

| Unless the master were the man. How now! Even so quickly may one catch the plague? | Olivia: (Act I, scene v) -- Monologue to Audience/ herself |

| But, come what may, I do adore thee so That danger shall seem sport, and I will go | Antonio: (Act II, scene i)—Monologue to audience/himself |

| I left no ring with her: what means this lady? Fortune forbid my outside have not charm'd her! | Viola: (Act II, scene ii) -- Monologue to audience/ herself |

| O time! thou must untangle this, not I; It is too hard a knot for me to untie! | Viola: (Act II, scene ii) -- Monologue to audience/ herself |

| Dost thou think, because thou art virtuous, there shall be no more cakes and ale? | Sir Toby: (Act II, scene iii)—Scene with Malvolio |

| Come hither, boy: if ever thou shalt love, In the sweet pangs of it remember me; | Orsino: (Act II, scene iv) -- Scene w/ Viola |

| It gives a very echo to the seat Where Love is throned. | Viola: (Act II, scene iv) -- Scene w/ Orsino |

| There is no woman's sides Can bide the beating of so strong a passion As love doth give my heart; | Orsino: (Act II, scene iv) -- Speech to Viola |

| I am all the daughters of my father's house, And all the brothers too: | Viola: (Act II, scene iv) -- Speech to Orsino |

| some are born great, some achieve greatness, and some have greatness thrust upon 'em | Malvolio:. (Act II, scene v) -- Speech to Audience/ himself |

| This fellow is wise enough to play the fool | Viola: (Act III, scene 1)—Speech to audience/herself |

| Then think you right: I am not what I am. | Viola: (Act III, scene i)—Scene with Olivia |

| I say, this house is as dark as ignorance, though ignorance were as dark as hell; and I say, there was never man thus abused. | Malvolio (Act IV, scene ii)—Scene with Feste |

| This is the air; that is the glorious sun; This pearl she gave me, I do feel't and see't; | Sebastian: (Act IV, scene iii) -- Speech to Audience/ himself |

| Do I stand there? I never had a brother; | Sebastian: (Act V, scene I) -- Scene w/ Viola |

| you shall from this time be Your master's mistress. | Orsino: -- Scene w/ Viola (Act V, scene I) |

| I’ll be revenged on the whole pack of you! | Malvolio (Act IV, scene i)—Scene with everyone |

| and thus the whirligig of time brings in his revenges. | Feste: (Act V, scene i) -- Speech to Malvolio |

| The rain it raineth every day. | Feste: (Act V, scene i)—Song to audience |

Curriculum Plan #2

Twelfth Night - The Musical!

Adapted from Craig Robertson South Grand Prairie High School in Grand Prairie, Texas,

Objectives: This activity allows students to reinterpret Act 2 of Twelfth Night as a musical, using contemporary songs. Students will discover the meaning of the text, the plot, and the relationships between the characters.

What You Need: Soundtrack to Moulin Rouge, Tape/CD player, a copy of Twelfth Night

This lesson will take 2 class periods.

Suggested Lesson Plan:

- Play the song from the Baz Luhrmann film Moulin Rouge entitled "Elephant Love Medley."

- Divide the class into five groups, and assign each group a scene from Act 2. Have each group read through its scene together twice: first, to brush up on the plot, and second, to divide the scene into units. Explain to the students that a new unit is created each time a character's intention in the scene changes, a new character enters the scene, or the scene begins to move in a different direction. Some groups will come up with many units, but tell them to try to limit the units to ten.

- Tell the groups that they will be creating a musical medley just as Baz Luhrmann did and that each unit will be replaced with a song of their choosing. Have the students discuss what is happening in each unit: is someone pleading to another? Is someone bragging? Is it a quarrel?

- Now, have them find contemporary songs to fit the basic ideas of the units. Tell them to choose songs that they have on CD or tape at home, because they will be playing the songs for the class the next day. You may also want to put in place some guidelines: for example, no profanity.

- On the second day, have the groups go to the front of the class in the order of their scenes. If time permits, have the groups read through the scenes; otherwise, have them briefly review the action of the scenes for the class. Then, have them play a bit of each song from their medleys. (Don't have them play the entire song, or this lesson will take a week to get through.) Ask each group to defend its choices. You may also want to discuss how music can help to clarify what happens in the play.

Assessment

Do your students better understand what is happening in their scene? Can they defend their choice of songs by referring back to the text of the play? Have the students' choices illuminated the text in some way?

Curriculum Plan #3

Malvolio Writes Back: Love Malvolio-Style

Adapted from Karen Richardson Westlake High School in Westlake, Louisiana.

Objectives: In this lesson students will use higher-order thinking skills to analyze the character of Malvolio and write a letter consistent with his personality and vocabulary as demonstrated through the text.

What You Need: A copy of Twelfth Night

This lesson will take one to two class periods.

Suggsted Lesson Plan:

- Review the letter Malvolio assumes is from Olivia. Discuss the reasons he is inclined to believe it is from her and the reasons he thinks it is written about him.

- Divide students into groups of three or four.

- Have students go to the text and list everything that other characters say about Malvolio in Acts I-III.

- Have student groups compose a letter of response to Olivia from Malvolio, incorporating the characteristics they have discovered. Then, have them write a rationale detailing the reasons their letter is consistent with Malvolio's character.

- Have the groups read and display their letters to the class. Conclude with a discussion of the different character traits on display and the different performance choices available to an actor portraying Malvolio.

Assessment

Were students able to select specific character traits to duplicate? Did their letters reflect the character of Shakespeare's Malvolio? Do the letters brighten up the walls of your classroom?

Curriculum Plan #4

Blame not this haste of mine": Creating a scene for Twelfth Night

Adapted from Megan Salomone of Byram Hills High School in Armonk, New York.

Objectives:

Shakespeare doesn't show the audience the conversation between Olivia and Sebastian after Act 4.1. However, the dialogue in Act 4.3 suggests that they have exchanged warm words. When the scene opens, Olivia has given Sebastian a pearl and is offstage fetching a priest. This section of the play offers an exciting opportunity for students to do some scene writing of their own. Writing a scene insert or an offstage scene requires close reading and a firm understanding of character. Furthermore, students take ownership of the play as they bring the characters to life.

Plays/Scenes Covered

Twelfth Night 4.3

What You Need

a copy of Twelfth Night

This lesson will take 1-2 class periods.

Suggested Lesson Plan

- Choose two students to read Act 4.3 aloud. Discuss the various sources of Sebastian's confusion and how he arrives at the conclusion that neither he nor Olivia is mad.

- Write the following writing prompt on the board: Why does Sebastian agree to marry Olivia so quickly? Discuss three possible reasons in detail.

- Give students five minutes to write; then ask a few to share their ideas.

- Divide students into groups of four. Tell them that they will be responsible for creating a brief scene that could logically fit between scenes 4.1 and 4.3. Ultimately, their scene will answer the writing prompt in more detail. Students do not have to use iambic pentameter

or imitate Shakespeare's style, but they should be as creative with language as possible. Encourage them to experiment with the words and images they have studied in the play.

5. Put the following information on the board or an overhead before the students arrive, but cover it so the students can't see it. After explaining the steps above, uncover the information. Each group will have four roles:

- 1 student to act as Recorder - to record the script as the group composes it together and help the presenter discuss the group's choices.

- 2 students to act as Actors - to play the roles of Olivia and Sebastian during the performance.

- 1 student to act as Presenter - to explain to the class the choices the group made while creating the scene.

6. As a group, discuss the following questions. The scene they write between Sebastian and Olivia should answer these questions in dialogue, from the point of view of the two characters:

Does Olivia discuss Toby's "fruitless pranks," as she says she will in Act 4.1? Does Olivia mention previous conversations she has had with Cesario?

- Who does most of the talking?

- What prompts Olivia to give Sebastian a pearl? What motivates Olivia to go find the priest?

7. Give students 20-25 minutes to create their scenes. Monitor them closely, offering suggestions and encouraging them to stay true to Shakespeare's characterization and plot details. They don't have a great deal of time, so it's particularly important that they make decisions quickly and stay on task.

8. One at a time, have the groups take the stage. After the actors perform the scene, ask the presenter and recorder to comment briefly on the choices they made while writing. Ask the audience members to discuss the differences between scenes. At the end of the performances, celebrate the students' work with a round of applause and a group stage bow.

Assessment:

Did students work together, have fun with language, and create scenes that came to life through performance? Don't worry about whether their scenes were brilliantly worded or theatrically captivating. The emphasis here is on the process of discussing character motivation and creating dialogue.

Curriculum Plan #5

Lights, Camera, Action

Adapted from Leigh Lemons of Marblehead High School in Marblehead, Massachusetts.

Objectives

In this lesson students will interpret Twelfth Night or another play by creating a silent movie, requiring them to think creatively and enhance their storytelling skills in verbal, nonverbal and written form.

Plays/Scenes CoveredTwelfth Night, or any of Shakespeare's plays.

What You Need

A copy of the play, video camera or still camera and scanner, computer lab access, technician or support teacher if necessary

This lesson will take approximately three class periods.

Suggested Lesson Plan

- Divide the class into five groups and assign each group one scene of the play.

- Tell students it is their task to create a silent movie of different tableaux to represent the most important developments in their scene of the play. The movie must have 5-10 "slides," frozen images that represent individual moments in the text. Each group member must participate.

- Have students begin by brainstorming ideas for the most important moments in the text, then choose a selective group of those moments for their movie.

- Before getting on their feet, have students create a storyboard for their important moments on paper. They can draw some quick sketches with stick figures. It helps if they give a title to each picture.

- Now it’s time for students to get on their feet. Have students represent their storyboard slides with real people in real space. Students should explore ways to represent each moment. Encourage them to experiment with different ideas before settling on one. Emphasize the importance of heightened nonverbal communication. Discuss facial expressions, gestures, stance, interaction and pose.

- Allow students time to rehearse their tableaux.

- At this point, the students may perform their tableaux with a live narrator as described in #9, or if you’re school has access to camera, video & computer equipment, you may want to proceed to #8.

- Showtime: if your school has a video camera, record the performances. If you have access to a scanner, you could photograph the slides and scan them as well.

- Using PowerPoint or other presentation software, have students add narration to the slides they have created. Finally, have students complete their movies with slides that introduce their work and its cast.

- Present the completed movie to the class and print a hard copy for public display. Conclude by discussing the differences in the choices made by the different groups, and the lessons students learned in the creation process.

Assessment

Did your students come to understand the most critical components of each act? Did they read the text closely and discuss it thoroughly? Did they learn any new technology? Did they learn kinesthetically? Did they work collaboratively? Did they respond positively

Curriculum Plan #6

The Case of Malvolio v. Maria, Sir Toby Belch, et al.

Objectives

Hold a classroom trial in which you explore the character of Malvolio and the actions committed against him in the play. In particular, the “practical joke” perpetrated against him by Maria and several of the other characters. The activity provides students with an opportunity to delve more deeply into the characters of the play and interpret the events of the play.

What you need

A copy of Twelfth night and the Who’s Who page from this study guide.

This lesson takes one to three class periods.

Suggested Lesson Plan

- Elect class members to serve in the following roles: judge, jury, defense team, prosecution team, and each of the characters listed in Who’s Who.

- Additional characters can be “created” by the defense and prosecution teams if they desire. For example, they may want to produce a kitchen cook or servant as a character witness for Malvolio. If additional characters are created, they can be pulled from the jury. But if a jury member becomes a character, they may not return to the jury. If you run out of students to form the jury, then the trial can

become a “hearing” before the judge (who might be played by the teacher.)

- Give the defense and prosecution teams time to prepare their cases, and witnesses the time to go over the facts of their stories with regard to the practical joke played on Malvolio. Students might need to review the play or the play’s synopsis for homework.

- Start the trial, beginning with the prosecution. Have each legal team call for witnesses, ask questions and present evidence against and in the defense of those who “wronged” Malvolio.

- At the end of the trial the jury (or judge) must pass their verdict. If guilty, they should also recommend a punishment suitable to the crime.

Assessment

After the trial, have the class answer the following questions: Do you agree with the jury’s verdict? Why or why not? Was Malvolio unfairly treated by the others? Did he do anything to bring such treatment on himself? Did your students delve more deeply into the characters? Did they read the text closely for their characters’ story.